By Matthew Putman

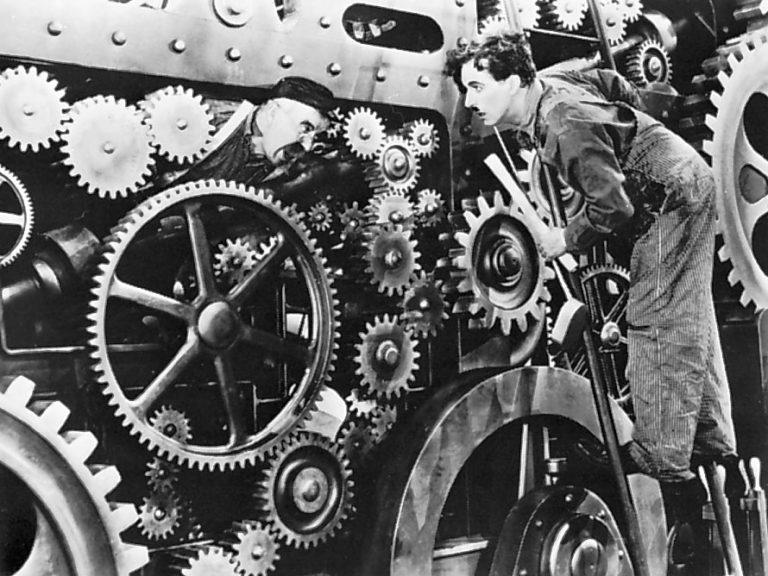

Still from Modern Times. Charlie Chaplin’s character inspects the giant gears of the factory machines.

In 1936, the year Hitler violates the Treaty of Versailles, Charlie Chaplin releases Modern Times. That year, Charlie Chaplin was the bigger star. The dictator militarized and fueled his propaganda machine. Chaplin transformed moving pictures forever.

Charlie Chaplin grew up in abject poverty. As a child he spent time in a workhouse. He based his iconic character “The Tramp” on these early struggles. A director, a writer, a composer, a producer, a founder of United Artists, and one of the most successful men of his time, Chaplin’s point of view always remains that of the underdog.

When Chaplin makes Modern Times it’s the Great Depression, and resentment and dread haunt the political landscape. Breadlines form outside the gates of brand-new factories. Chaplin, a keen observer of his times, makes technology the subject of his latest film. Doing so ensures that the machine never has the chance to upstage the man.

The director delivers a powerful message about the dangers of mechanization by dancing into his ‘story of industrial revolution.’ His factory worker mocks machinery as he celebrates it with his own marionette-like body.

Chaplin was an artist of his times: prolific, acrobatic, absurd, and fast. By Modern Times Chaplin had become one of the most technically inventive filmmakers in history. He experimented with lenses, camera movement, and evolving sound technology.

The machines gobble up Chaplin’s character in Modern Times, only to spit him out. Chaplin himself was subject and master to technology. The camera swallowed his image only to project his likeness across millions of eyes in dark theaters all around the world. He submerged each invention that rolled off factory floors into his art—with the same factory-like industriousness of the greatest 20thcentury magnates and inventors.

***

Inserting ideas into comedy was an absolute necessity in 1936—but this impetus weathers crisis and medium. I see the same necessity today.

In our own way, each of us feels the weight of balancing commercial demand and social need, especially where technology and media intersect. This split identity is at the heart of the film medium from its beginnings. Thomas Edison created the motion picture as a voyage into something never before experienced. As a scientist, he didn’t initially see its potential as an artistic form.

Chaplin explored cinema to bring physical comedy to large groups of people, but not only that. He avoided pressures to compromise his vision—not due to any reactionary tendency, but to allow himself to fully master the possibilities of a relatively new form as talkies became prevalent. When he gave into the pressures to speak, he enhanced lines and monologues without sacrificing physicality.

In the desperation of the great depression, from his observations working on a printing press and witnessing a Ford assembly line, Chaplin felt the risks of industrialization. Yet there was ambiguity in his relationship to industry. Chaplin was also someone who believed in machines.

His later film, The Great Dictator (1940), ends with one of the most powerful speeches I’ve ever heard:

“Do not despair. The misery that is now upon us is but the passing of greed – the bitterness of men who fear the way of human progress.”

“You, the people have the power – the power to create machines. The power to create happiness! You, the people, have the power to make this life free and beautiful, to make this life a wonderful adventure.”

When I watch Modern Times and The Great Dictator, I see a glimpse of the possibility for machines to become tools for good. I aspire to reflect this beauty in Nanotronics’ greatest discoveries. These discoveries exist for others to create, explore, and invent with for the AI era, I hope they give a fraction of the possibilities of the electric light and motion pictures of Edison’s lab.

Whenever the future seems uncertain, wobbly, or dark, I remember Chaplin and Paulette Goddard shuffling into the glittering night at the end of Modern Times together—and the look on my son’s face the first time I showed him the film.