By Matthew Putman

Scientific knowledge is the methodical exploration of nature through experimentation.

Knowing is the fabrication of new objects. This is where engineering comes from: a truly ancient skill, an artifact of our collective human past.

Last week I was generously invited to Columbia University* to see a project that involves encoding and translating a sixteenth century French manuscript—creating a digital incarnation that will allow it to survive and be seen by a much wider audience than was ever possible in its physical form. The book is one of the most human things: a glossary of techniques, terms, and tools for building. It’s at once a library of knowledge, an investigation, and an apparatus for molding matter using the written word.

***

It struck me, as just a few days prior, I was thinking about how close we are to replacing the majority of manual labor with automation. Any given piece of furniture or object in your home—a chair, a desk, a lamp, a woven rug, a book, is touched by dozens of human hands on its way to you. What if that were no longer true?

What is the meaning of human touch in the fabrication of our most personal objects—the materials that envelop us, shelter us, and protect the tools we build with?

As I walked out of Nanotronics’ production room, I was taken aback, and, given an answer of sorts.

Danielle Pucciarelli, an R&D intern, was literally sculpting clay with her hands. As she took a steel scraper and cut into the block, I was enthralled by the effect of juxtaposition. The oldest material in the world, the earth, being sculpted into shapes that would mold the hood of a tool that would be used to enable one of the most all-encompassing of human projects…complete genomic sequencing!

Damas Limoge’s team was experimenting with a complex microscope enclosure that will house irregularly shaped robotics, for nSpec®, which they will eventually manufacture using 3D printers. In a few short weeks, this enclosure will find a home in clean rooms and intelligent factories.

Danielle and Husna Ellis, her teammate, explained that they wanted to use their hands to experiment with the general shape of the enclosure rather than immediately modeling it in CAD. Craftmanship. Experimentation. Hands full of dirt. It was the most human desire possible.

***

Creators, technology, tools, and craftsmanship are aligning in spellbinding ways through the use of AI. The clay was tangible. It would be turned into a digital file. That file would then turn into a printed part. That part would then be optimized using AI, which would find the least wasteful way to fabricate its shape, in its own simulation of experimenting and learning.

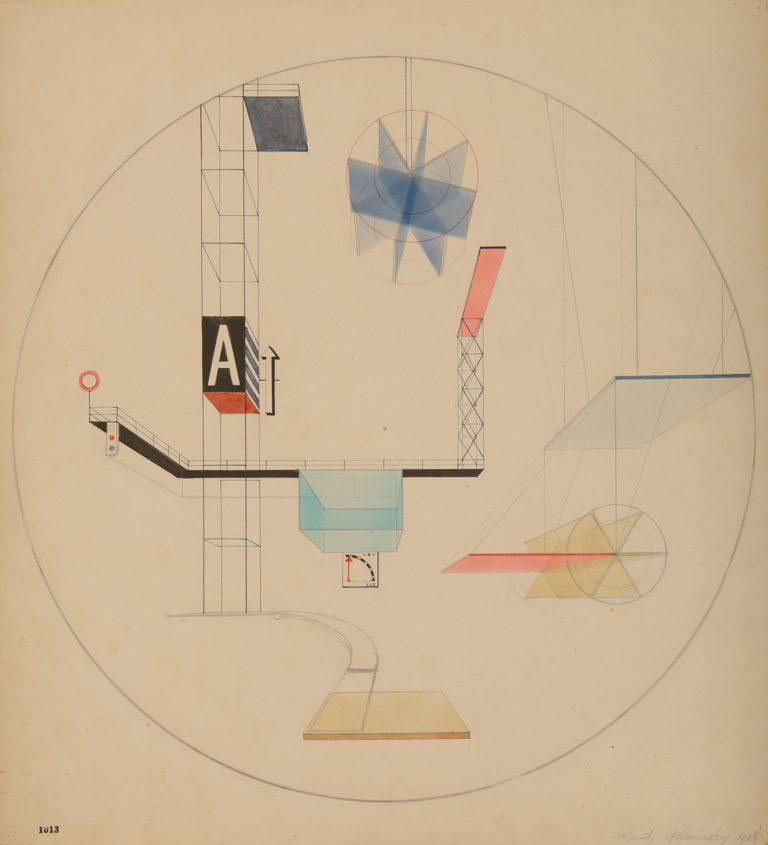

Travelling through time, my mind skips to Germany between the wars—Bauhaus. Literally, it translates to a house for building. As mechanization flourished, one of Walter Gropius’ goals was to recombine craft with fine art, engineering, and architecture. Another was to build unique, modular pieces and parts for living. Closing the schism between craft, industrial production, and the individual. One of the first exercises every Bauhaus student does is cut into squares of colored craft paper to make shapes and collages; a deceptively simple hands-on first lesson. A step toward understanding the endless possibilities of play between color and geometry; the fundamentals of form and composition.

In 2019, the 100th anniversary of Bauhaus, processes for advanced manufacturing seem complex by nature. But in fact, it’s simpler and cleaner than ever to produce the fantastic, functional machines we imagine. The path from brain to production line has gone full circle, in a way. For the first time in a century of industrial manufacturing, because of AI, formally rigorous, functional objects are modifiable—individually—at production scale.

Gropius wrote in 1919, in the Bauhaus Manifesto:

“This world of mere drawing and painting of draughtsmen and applied artists must at long last become a world that builds…Architects, sculptors, painters—we all must return to craftsmanship!”

Today, at Nanotronics, the Bauhaus dream feels closer than ever.

Image Credit: Xanti Schawinsky, Design for a constructivist stage set, 1926. (Image: © Xanti Schawinsky Estate)

* The Making and Knowing Project, started by the Center for Science and Society is at once a laboratory, testbed, and preservation effort. Their goal is to re-center artisanry and craftmanship at the heart of our understanding of any form of knowledge.